Concept: Skinscapes, a MoMA Exhibit

Photographing women’s skin in feminist activism and art.

“The styled body is a sincere identifier of the individual within an activist movement. How someone chooses to style themselves, to construct their sense of self, is agency.”

—Tulloch, Carol (2019) ‘Style Activism: The Everyday Activist Wardrobe of the Black Panther Party and Rock Against Racism Movement’ p. 85.

Across the globe, people protest for rights, visibility, acceptance, and peace. They hold up signs, march, strike, lobby, vote, and petition. The tactics used in protest are sometimes integral to its success or social impact. For example, The Black Panthers were recognized for their distinctive black clothing and berets, which symbolized unity. The use of the color red in protests for missing and murdered Indigenous women signifies voices that have been silenced. The act of removing a hijab in the Freedom Life movement embodies the struggle against systemic oppression faced by women in Iran. These examples share a commonality: They utilize dress, garments, or colors in political protests, also known as vestimentary protests.

For my final project in Fashion Theory, the example of vestimentary protest that I focused on was the skin. Through a compelling collection of photographs, photo-collages, and multi-media art primarily originating from female artists, I created a concept exhibit for the MoMA titled Skinscapes. The visual medium of a museum exhibit was a unique idea to present my topic of women’s skin as a recurring vestimentary symbol in feminist subcultures. The exhibit examines how skin—marked, exposed, and written upon—becomes a powerful medium for challenging societal norms, reclaiming agency, and asserting identity.

This is a student project. I do not claim the rights to any images used.

A MoMA Exhibit: Skinscapes*

Photographing women’s skin as a recurring vestimentary symbol within feminist activism & art

16-25 November 2024

11 West 53 Street, Manhattan Floor 3, 3 South

The Edward Steichen Galleries

*Exhibit title derived from chapter of the same name from Pierced Hearts and True Love : A Century of Drawings for Tattoos by Don Ed Hardy

“The body is a temple to be decorated.”

—Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. 2012. From the Stigmatized Tattoo to the Graffitied Body: Femininity in the Tattoo Renaissance. p. 9.

The Skin as a Canvas

Architect Pallasmaa notes that our sense of touch is essential to understanding and being with the world, as the skin is our largest organ. Anthropologist Schildrout highlights that the skin serves to define individual identity and cultural differences.

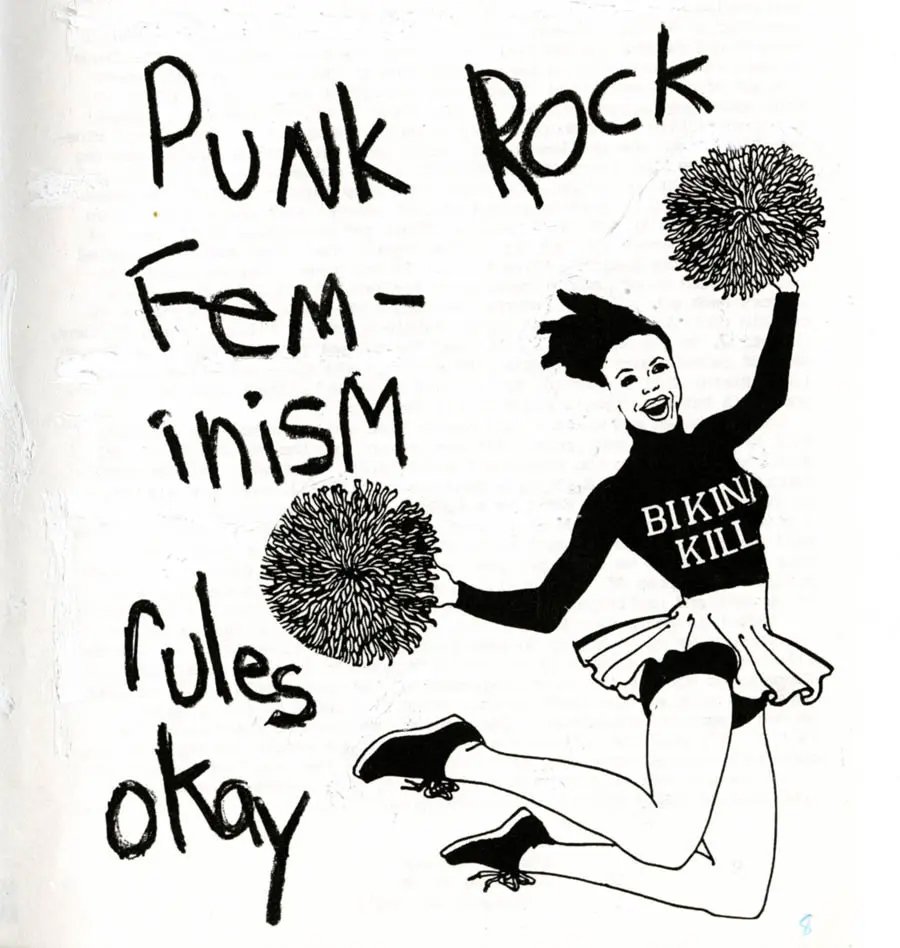

Feminist subcultures, such as the Riot Grrrls, use the skin for "body writing," while the Suicide Girls employ heavy tattooing as a medium to express identity and empowerment, challenging societal norms and redefining beauty and bodily autonomy. Conversely, the naked [female] skin is also a site of vestimentary protest.

Explore Works from “The Skin as a Canvas”

The Written Skin

Sociologist Van De Velde expresses that words are central to social movements, especially when they are found on clothes, bodies, and faces. Feminist writer Cixous argues for women to “write” themselves, that “it is time for women to start scoring their feats in written and oral language.”

The Riot Grrrl movement took the feminist call for self-expression through language and turned it into a bold and unapologetic form of bodily activism. Kathleen Hanna, the most visible figure of riot grrrl, pioneered body writing and word reclamation as an activist practice. At a Bikini Kill performance in Washington, D.C., in June 1991, she famously wrote "SLUT" across her exposed stomach in black marker, reclaiming a term used to shame women in a culture that objectifies their sexuality while simultaneously condemning them for it.

SlutWalk protesters picked up the tactic of body writing from Riot Grrrl feminism. Their goal is to combat sexual assault by challenging degrading words, like slut, and re-frame them in a subversive way that is actually positive and respectful. The criticism this takes can be seen in an open letter from black women to SlutWalk, where they react and explain there is no place for black women to participate in this movement.

Explore Works from “The Written Skin”

“On a woman's body any tattoo becomes the symbol of bodily excess. When a woman's body is a sex object, a tattooed woman's body is a lascivious sex object; when a woman's body is nature, a tattooed woman's body is primitive.”

–Megan Jean Harlow. “The Suicide Girls: Tattooing as Radical Feminist Agency.” p 186.

The Tattooed Skin

In today’s image-dominated culture, everything is designed for display but remains untouchable; eroticism has shifted into voyeurism, where connections to the real body are obscured by visual consumption, perfume, and medicalization. Tattoos, particularly on women’s bodies, carry layered meanings—symbols of excess that disrupt traditional categorizations.

Suicide Girls is a website that hosts sexually explicit images of women who are not the typical Playboy model, often bearing heavy tattoos, piercings, and other punk aesthetics. The website itself uses feminist rhetoric to redefine beauty through these girls who commit social suicide and assert their own version of beauty.

Criticism does exist for Suicide Girls, that displaying tattooed women, even within a platform that claims to empower them, can still contribute to sexual objectification. Critics might point out that the male gaze is still very much present in the Suicide Girls platform. Atkinson's research acknowledges the popular narrative that women get tattoos as acts of rebellion.

Explore Works from “The Tattooed Skin”

“Naked female bodies have a different visceral and political significance and resonance to male bodies”

—Jacki Willson. “Fashion, Performance, and Performativity: The Complex Spaces of Fashion.” pp 100.

The Nude Skin

Depictions of the nude in art are influenced by the dominant fashion conventions of their time, meaning that the nude is never truly naked but "clothed" by those conventions. The female body has always been mediated to give a visceral significance, with systems of shame and disgust setting limits to what is socially acceptable gendered behavior.

Feminist media scholars Thomas and Stehling argue that naked protests are a global phenomenon where the bodies become the medium and the message. Though there are many protests where nudity is the tactic, FEMEN is the pinnacle example. In 2008, FEMEN wanted to make sure that “people would no longer ignore the aggressive marketing for the sex industry” in preparation for the European Soccer Championship in Ukraine.

Like how tattoos disrupt the ideal of the unmarked, pristine body, FEMEN's naked protests can be seen as a radical rejection of the societal expectation for women to conform to specific standards of modesty. These protesters bare their bodies and also almost always feature body writing . FEMEN’s protests bring forward the question of whether using nudity is capitalizing on the male gaze and if nudity turns their protests into spectacles, taking away from their actual message.

Explore Works from “The Nude Skin”

In conclusion, this exhibition displays how women's skin is a powerful, recurring symbol within feminist activism and art. It showcases how marked skin, through tattoos and body writing, challenges societal norms and reclaims agency, while nude protests, like those by FEMEN, disrupt ideals of modesty and purity. However, these forms of protest come with complexities—whether it's the risk of reinforcing the male gaze or upholding narrow beauty standards. The question that remains top of mind for each viewer as they exit the exhibit is this: How can feminist activism continue to use the skin as a site of resistance while ensuring inclusivity and avoiding unintended objectification?

A creative mind and design professional, Julia is an Art Director, Senior Graphic Designer, Beauty Enthusiast, and a Master's Student in Global Communications. This blog is an extension of her multi-faceted journey, offering a space to explore the intersections of design, beauty, culture, and lifestyle

Bibliography

Atkinson, Michael. “Pretty in Ink: Conformity, Resistance, and Negotiation in Women’s Tattooing.” Sex Roles, vol. 47, no. 5/6, Sept. 2002, pp. 219–35. ProQuest, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021330609522.

Blueprint, Black Women’S. “An Open Letter from Black Women to the Slutwalk.” Gender and Society, vol. 30, no. 1, 2016, pp. 9–13.

Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. “From the Stigmatized Tattoo to the Graffitied Body: Femininity in the Tattoo Renaissance.” Gender Place and Culture - GEND PLACE CULT, vol. 20, Jan. 2012, pp. 1–17. ResearchGate, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2012.674930.

Cixous, Hélène, et al. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–93.

Entwistle, Joanne. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Social Theory. John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

Harlow, Megan Jean. “The Suicide Girls: Tattooing as Radical Feminist Agency.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, Jan. 2008. www.academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/342084/The_Suicide_Girls_Tattooing_as_Radical_Feminist_Agency.

O’Keefe, Theresa. “My Body Is My Manifesto! SlutWalk, FEMEN and Femmenist Protest.” Feminist Review, vol. 107, no. 1, July 2014, pp. 1–19. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2014.4.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aup/detail.action?docID=896076.

Perry, Leah. “I Can Sell My Body If I Wanna: Riot Grrrl Body Writing and Performing Shameless Feminist Resistance.” Lateral, no. ateral 4, 2015. csalateral.org, https://doi.org/10.25158/L4.1.3.

Reckitt, Helena. The Art of Feminism, Revised Edition. Chronicle Books, 2022.

Schildkrout, Enid. “Inscribing the Body.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 33, 2004, pp. 319–44.

Snow, David A., et al. The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2007. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aup/detail.action?docID=351505.

Thomas, Tanja, and Miriam Stehling. “The Communicative Construction of FEMEN: Naked Protest in Self-Mediation and German Media Discourse.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 86–100. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1093111.

Van De Velde, Cécile. “The Power of Slogans: Using Protest Writings in Social Movement Research.” Social Movement Studies, vol. 23, no. 5, Sept. 2024, pp. 569–88. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2084065.

Willson, Jacki. “The Fashioned Female Body, Performativity, and the Bare.” Fashion, Performance, and Performativity : The Complex Spaces of Fashion, edited by Andrea Kollnitz and Marco Pecorari, 1st ed., Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2022, pp. 97–114, https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/encyclopedia-chapter?docid=b-9781350106215&tocid=b-9781350106215-chapter5. Bloomsbury Fashion Video Archive~Bloomsbury Fashion Video Archive 2020 collection~Bloomsbury Fashion Video Archive 2021 collection~Bloomsbury Fashion Business Cases~Fashion Photography Archive~Fairchild Books Library~Berg Fashion Library~Bloomsbury Fashion Video Archive 2022 Update~Bloomsbury Fashion Business Cases 2022 Update~Berg Fashion Library 2022 Update~Berg Fashion Library 2023 Update~Bloomsbury Fashion Business Cases 2023 Update~Bloomsbury Fashion Video Archive 2023 Update~Bloomsbury Dress and Costume Library~Berg Fashion Library 2024 Update~Bloomsbury Digital Fashion Masterclasses~Bloomsbury Dress and Costume Library 2024 Update~Bloomsbury Historic Dress in Detail~.